Acrylic Films which Destroy Viruses with Nano-pillars

The latest nanotechnology discovery shows how polymer shape at the nanoscale can kill viruses on contact.

Manufacturers have become used to the advances which nanomaterial science is providing the polymer sector. But what if it was possible to design a polymer surface that actively neutralises viruses without chemistry? That’s exactly what a recent breakthrough in mechano-virucidal nanostructures promises to deliver.

Typical antiviral coatings rely on chemical agents — metals like silver or copper, or biocides that release toxins. These can be effective, but they bring concerns about environmental persistence, material degradation, cytotoxicity, and even the emergence of resistance.

Related articles: Where Nanostructured Polymers are Advancing Industry and On-Demand Biocide for Glass, Plastic and Metal

But the latest nanotechnology research flips this approach to cleanliness on its head by replacing chemistry with geometry.

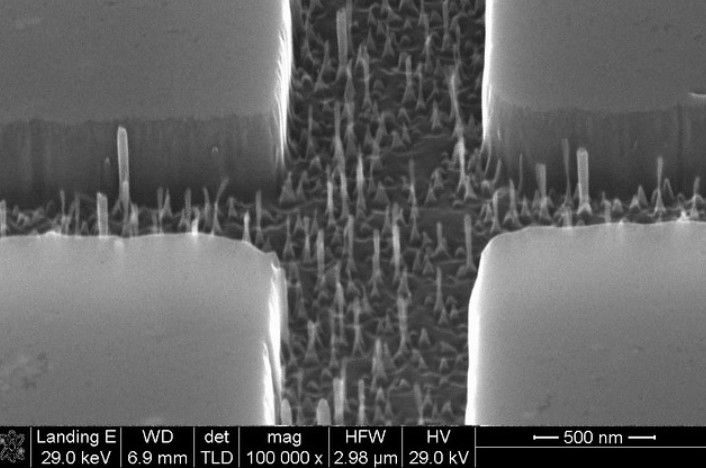

The core of the new concept is based on sculpting the surface of a polymer film at the nanoscale so that it mechanically disrupts virus particles on contact. This mechano-virucidal approach borrows from and extends earlier work based on nanoscale structures that could physically break bacteria membranes through mechanical stress. By tailoring nanoscale topography to match the dimensions and mechanics of viruses, nanomaterial researchers have created polymer surfaces that can literally kill viruses without chemicals.

How Nanopillars Destroy Viruses

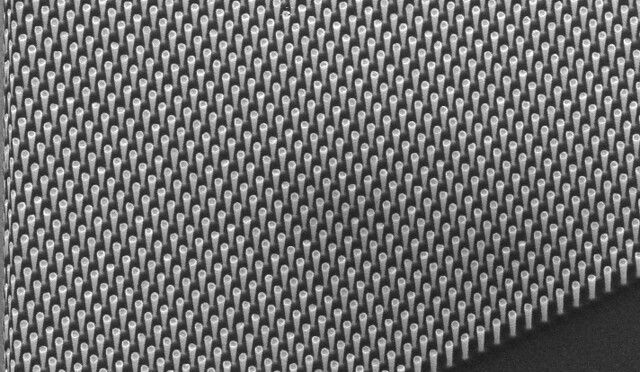

The study was based in Australia’s RMIT University and lays out a clear design principle: arrays of tiny polymer nanopillars with precise pitch (spacing) and height can generate stresses large enough to exceed the rupture threshold of a virus’s envelope. Significantly, the research team used ultraviolet nanoimprint lithography (UV-NIL) with anodised aluminium templates to create flexible acrylic films patterned with regular nanopillars.

By systematically varying the spacing and height of these nanopillars, they found that:

· Tighter spacing (~60 nm) produces a high-level antiviral effect, with a 94 % reduction in the infection ability of human parainfluenza virus type 3 within just one hour of contact.

· Wider spacing (>100 nm) weakens the effect, and at ~200 nm the efficiency of the antiviral property essentially disappears.

· Computational modelling shows these dense arrays produce local stress fields exceeding the estimated ~10 megapascal rupture limit of the viral envelope, physically disrupting the particle.

In simple terms, these are polymer surfaces that don’t poison viruses — they physically challenge them at a scale where their own structure gives way.

Why This Matters for Polymer Manufacturers

From a business perspective, this research is groundbreaking, as it removes the need for scarce and potentially toxic agents by replacing them with topographical engineering. The nanoscale shape of the polymer is enough to keep it clean.

Additionally, the use of acrylic films and imprint techniques in the experiments points to methods that can be scaled beyond lab samples toward industrial production.

It also opens up a range of industrial applications where antiviral protection is a key element and valuable sales point. These include:

· Healthcare and food preparation environments—such as door handles, bed rails, or hospital instrument surfaces where surface-transmission risk is high.

· Public transport and shared spaces—buttons, handrails, and counters in buses, trains, elevators, and shops where virus persistence could be reduced without chemical wiping.

· Consumer electronics—mobile phone screens and digital interfaces, such as touchscreens or keypads, could use nanotechnology to manage viral contamination passively.

Notably, this approach could also complement ongoing work in antiviral coatings and filtration, offering a mechanical guard that works alongside chemical and biological strategies rather than replacing them altogether.

The discovery also creates new clear design rules which offer a roadmap for further improvements and expansion on how nanomodification of polymers can provide enhancements and added properties. This could open doors to multifunctional polymers that combine mechanical robustness, antiviral action, and other performance attributes, such as boosted mechanical strength or optical transparency.

This new mechano-virucidal strategy turns nano-engineering into a proactive defence for polymer surfaces. In a world where viral threats — whether seasonal flu, common respiratory viruses, or emerging epidemics — are part of the public consciousness, solutions that embed protection into the very structure of materials are both elegant and pragmatic.

A future where, for polymer researchers and plastic businesses alike, this isn’t just about reducing the spread of viruses — it’s about rethinking what polymer surfaces can do.

Photo credit: Dragana_Gordic, Flickr, & Flickr