Why Nanofabrics Matter Beyond Textiles

Nanofabric technology represents a real opportunity for manufacturers to gain a competitive advantage.

Despite the name, nanofabrics are not a textile story—they are a surface engineering breakthrough for polymers and coatings.

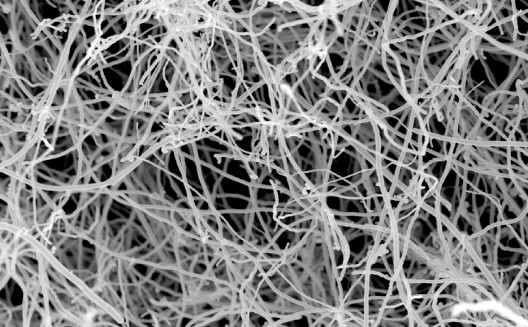

At their core, nanofabrics rely on nanoscale surface engineering: the use of nanomaterials and nanostructured coatings to modify how a material behaves without fundamentally changing its bulk composition. This principle is increasingly important in various manufacturing sectors, such as in the production of paints, resins, membranes, and polymer films. In fact, nanotechnology in this field is impacting all manner of composites.

For manufacturers, nanofabrics are best understood not as textiles, but as polymer substrates enhanced through changes to a raw material’s surface at the nanoscale. A similar approach is used to give face masks antimicrobial properties, or clothing water repellence or breathability. But now the technology can now be transferred directly to engineer the polymer surfaces used in construction, transport, medical devices, and everyday plastics.

Superhydrophobic surfaces, for example, reduce fouling and cleaning requirements on polymer components, while antimicrobial coatings extend the service life of polymer parts used in healthcare, food processing, and water treatment. Additionally, UV-resistant nanocoatings can help protect polymers used outdoors or in extreme environments from degradation. In the packaging sector, nanomodification of polymers allows for products to be sealed to a near-molecular level. Alternatively, breathable yet liquid-repellent surfaces can be created for industrial membranes or filtration systems.

Crucially, these effects are achieved without significantly altering the mechanical behaviour of the base polymer. For manufacturers, this means existing resin systems and processing machinery can be kept, reducing the cost of adoption.

Nanofabrics as a Concept for Surface Nanomodification

In nanofabric technology, functionality is typically introduced at the surface level rather than through the bulk modification of fibres. This is a distinction which is crucial for industry, as traditional polymer compounding often requires higher filler loadings to achieve mechanical or functional improvements (possibly negatively affecting processability, weight, and cost); nanocoatings allow manufacturers to tailor surface behaviour while preserving the desirable properties of the underlying polymer or resin.

This approach aligns well with current industrial priorities: lightweighting, material efficiency, durability, and extended service life. It means that a nanocoated polymer surface can deliver performance that would otherwise require more expensive base materials or thicker protective layers.

Key Nanomaterials Used in Nanofabric-Inspired Coatings

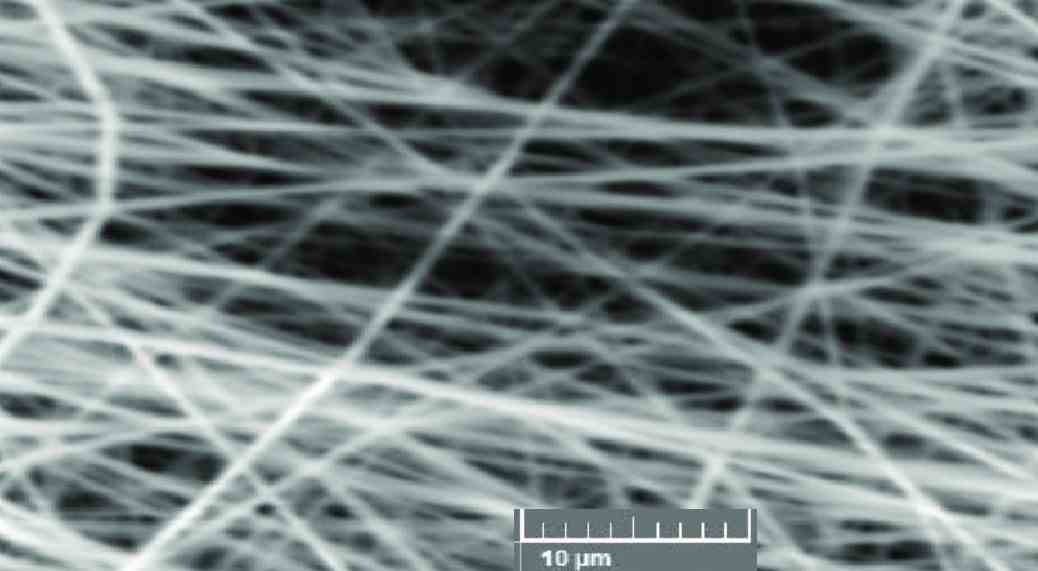

The nanofabrics field has driven the development and industrialisation of several nanomaterials that are now finding wider use in polymer coatings and surface treatments. These include:

· Silica nanoparticles, widely used to improve abrasion resistance, surface hardness, and scratch resistance.

· Metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles, particularly silver and zinc oxide, to provide antimicrobial, UV-blocking, or catalytic functions.

· Carbon-based nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and graphene, enabling electrical and/or thermal conductivity as well as mechanical reinforcement.

· Polymer-based nanolayers, designed to modify surface energy, permeability, or chemical resistance.

Crucially, these materials are typically applied in exceptionally low concentrations, making them attractive from both a cost and regulatory standpoint when compared with traditional fillers or additives.

For manufacturers considering how to add value to existing products, scalability is often the deciding factor. While some nanofabric techniques remain best suited to high-value applications, others have already demonstrated compatibility with roll-to-roll processing, spraying, dipping, and other continuous coating methods commonly used by manufacturers.

Sustainability and Lifecycle Impact

One of the strongest arguments for nano-enabled polymer coatings is sustainability, as by functionalising only the surface, manufacturers can reduce raw material consumption while extending product lifetimes. For end-use customers, this improved durability and resistance to fouling or degradation translates into lower maintenance costs, fewer replacements, and reduced waste.

Related articles: Nanotech Used in Novel Anti-Corrosion Polymer Coating or Beyond Kevlar: Nanotech for Bulletproof Polymer Fibres

How to Apply Nanofabric Technology to Products

For many manufacturers, the challenge is not a lack of interest, but a lack of certainty around material selection, processing compatibility, cost–performance trade-offs, and regulatory requirements. By combining applied research with pilot-scale testing, specialist nanotechnology centres can de-risk adoption, demonstrating how nanomaterials and nanocoatings integrate with existing polymers, resins, and production lines.

Companies such as POLYMER NANO CENTRUM (who host this webpage) play a critical role in helping firms translate nanotechnology from laboratory potential into industrial reality. They support manufacturers in optimising formulations, validating long-term performance, and scaling up from proof-of-concept to commercial output, while also addressing sustainability and compliance considerations.

The outcome is that nanofabrics should be viewed as a tool for improving all manner of manufactured products rather than a niche textile innovation. They demonstrate how nanoscale engineering can unlock new performance levels in polymers and coatings without fundamentally changing established materials or processes. For SMEs this represents a real opportunity to gain a competitive advantage, improve environmental credentials, add unique selling points, and even lower input costs.

Photo credit: Researchgate, Wikimedia, Wikimedia, & Wikimedia