Making Advances in Underwater Military Drones a Reality

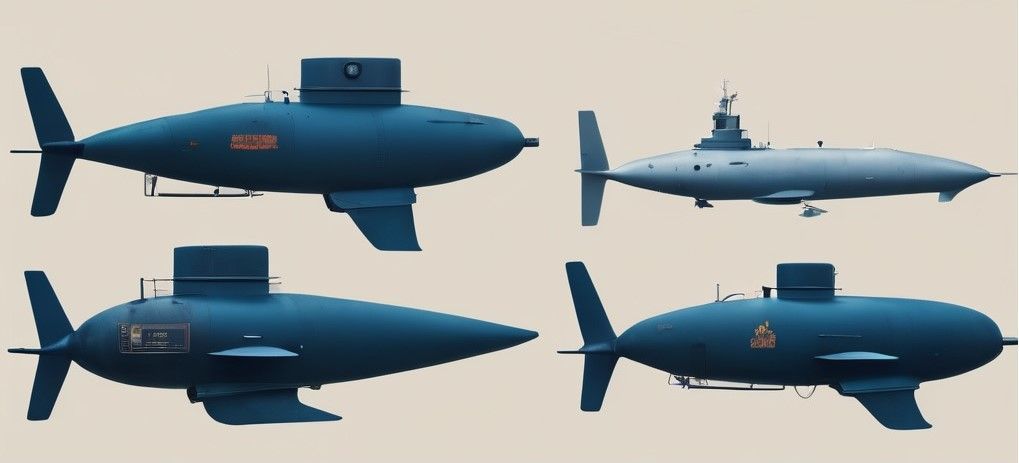

Are submarine-launched underwater drones the next phase of weapon development?

Progress on improving aerial drones for the military have been flying ahead. Development of remotely controlled sea-surface drones in both surveillance and combat roles have also seen great advances and even success in attacking Russian vessels in the Ukraine war. Land drones to assault trench systems or help navigate minefields have also come a long way in the last few years.

However, the concept of a military standard underwater drone capable of launch and recovery from a submarine has yet to be fully realized. Until now, because if the latest reports are to be believed, the US Navy is getting close.

According to a report in the industry journal Defense News, a medium-sized uncrewed underwater vehicle (UUV) should be operational “within the next several years.”

Designed to carry out expeditionary missions and mine countermeasures, while being launched and recovered from a submarine, the creation of a workable UUV would be a major advance in weaponry, especially with tensions running high in both the Arabian Gulf and the South China Sea.

Early research created a system known as Razorback – a medium-sized UUV that was launched and recovered from a submarine’s special operations dry deck shelter. However, this requirement made it labour-intensive and suitable for only the small number of US submarines capable of operating the technology. Consequently, its development was halted.

Instead, the current focus is on a drone that is launched and recovered from a torpedo tube allowing any submarine in the fleet to become a ‘drone mothership.’

“I think we are very close to deploying a torpedo tube-launched and -recovered UUV here within the next year,” explained Rear Adm. Rob Gaucher, Special Assistant at U.S. Fleet Forces Command and the nomination for Commander Submarine Forces. “So that’s going to be a big deal for us because success in that space is going to allow us to start operating at scale and putting these capabilities on every submarine.”

Recent testing by Submarine Force Atlantic was conducted on a drone called Remus UUV, while Submarine Force Pacific conducted “a similar Rat Trap exercise, where it successfully launched and recovered an L3Harris-made UUV from a submarine torpedo tube.”

“There is a plan in place to deploy that in 2024,” noted Gaucher when speaking at the Naval Submarine League’s annual symposium last month. “Now, will we get there? We still have some testing to do, but that’s our plan and that’s what we’re shooting for.”

Specifically, Gaucher confirmed that UUVs have already carried out eleven real-world missions in cooperation with European allies. These were largely counter-mine operations, but reconnaissance work had also been conducted, with submersible drones surveying the Nord Stream natural gas pipeline in the Baltic Sea.

Meanwhile, UUVs have also carried out harbour defence operations, as well as seabed and harbour surveys in the Middle East. Additionally, in order to prepare for future cooperation between the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, have taken part in ten exercises in the Pacific with four allies and partners that involved mine countermeasures and mining operations. Submersibles also engaged in an Integrated Battle Problem exercise that concentrated on subsea and seabed warfare.

While this progress has been made, there is still some way to go before uncrewed underwater vehicles are frontline operational. In its nature, water is deep and dark, contains strong currents, is hard to navigate, is limiting in terms of guidance via sonar or radar, and adds enormous pressures to any structure immersed in it. In addition to this, as an underwater weapon, remaining silent and undiscovered is also a priority.

In this sense, the weapons researchers have their work cut out for them.

As Capt. Jason Weed, US Navy Unmanned Undersea Vehicles Squadron, notes, “We have to tackle the technology challenges that we face with UVs; navigation, battery longevity, data management, common planning software, open architecture for payload integration, automatic variable ballast systems for our small and medium vehicles, communications both below water and above the water, interface and system autonomy are just a few of the challenges we're looking to tackle.”

Overcoming these challenges and advancing uncrewed underwater vehicle technology will take time, money, and innovation. However, more than that, as every entrepreneur acknowledges, the creation of something novel requires taking chances, even if it means sometimes failing.

As Capt. Weed confirms, “to help us reach the unmanned tipping point, just like naval aviation [development] was able to do over a hundred years ago, the first issue we have to tackle is our acceptance of risk.”

Photo credit: Walz from Pixabay, Gencraft,Unsplash, & Freepik