How The War in Ukraine Has Changed the Drone Manufacturing Sector

A case study of Estonian drone companies and their adaptation to frontline demands.

To see how far the drone industry has come since the war in Ukraine began, it is worth considering how Estonia’s drone manufacturing companies have adapted. It is a tale of quick reaction to customer demands and of rapid technological progress. But it is also a story of survival, both for business and for soldiers at the front line.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, drone designers and manufacturers focused on hardware which could provide for the commercial market by carrying a camera or helping fight fires, or maybe they were just low-cost models for the hobby market. Sales were based on practical commercial uses with little thought of arms manufacturing.

Fast-forward a few years and demand is now led by soldiers on the battlefield who need drones to work as reconnaissance units, artillery spotters, tank-busters, or in carrying heavy loads of supplies and ammunition to the frontline.

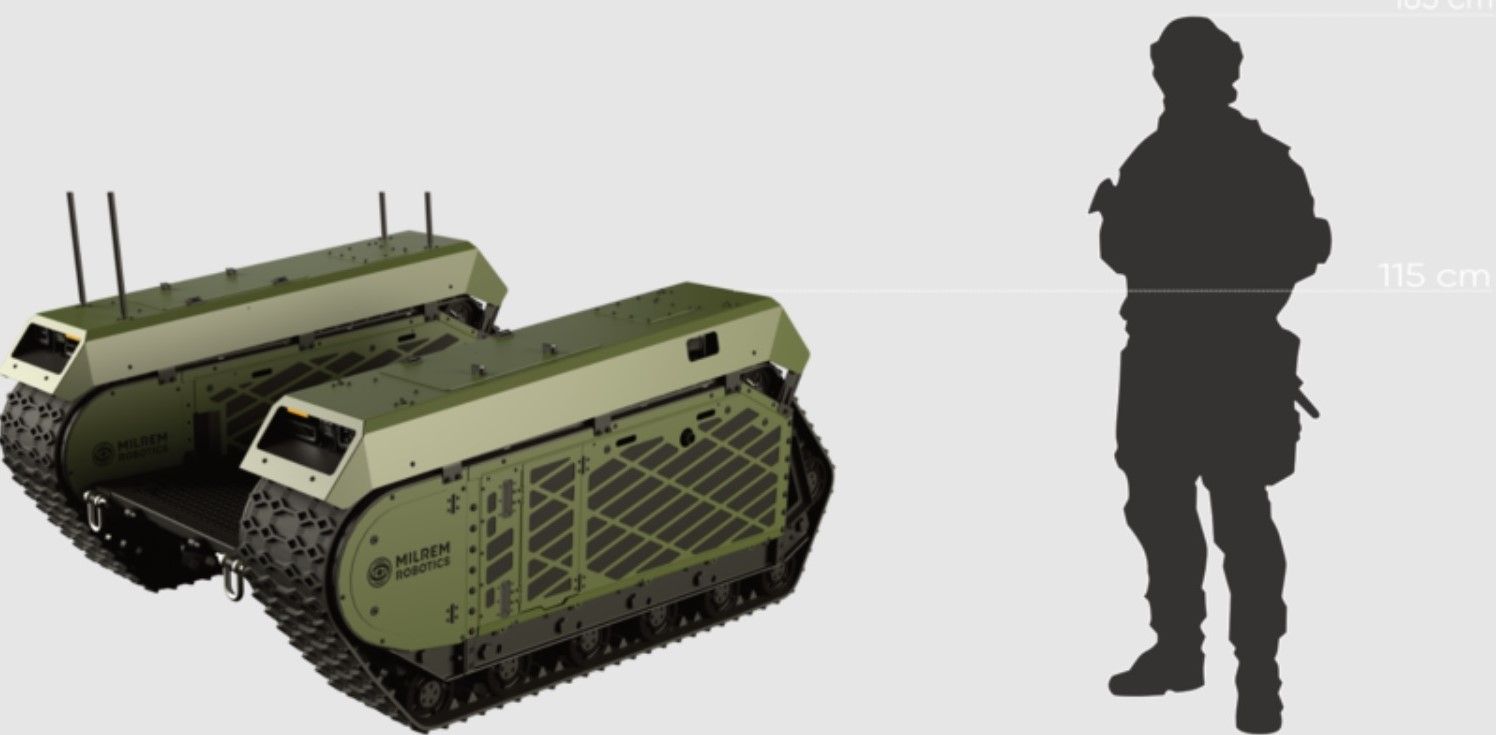

Like other drone manufacturing companies, Milrem is a relatively new and small operation. It started out in Estonia in 2013 making land-drones and robotic vehicles about half the size of a car. These were sold as load-carrying robots for commercial purposes, but some were also supplied to the military to assist in transporting heavy loads across inhospitable terrain.

This led to some of the vehicles being used in counter-terrorism operations alongside Estonian troops deployed in Mali.

This real-world experience of operating in combat zones has helped the company and its products adapt quickly to the needs of soldiers in Ukraine. As a result, in December 2022, the German government bought and then donated fourteen of Milrem’s THeMIS vehicles to the Ukrainian frontline to help deliver supplies, evacuate the wounded, and clear paths for supporting soldiers.

"Once the war in Ukraine started,” recalls Raul Rikk, the company’s capability development director, “we just put all these different [commercial] developments aside.”

As a nation, Estonia has been a major supporter of Ukraine’s defence. Thanks to its 340km-long border with Russia and its own history of Soviet occupation, Estonians have contributed more as a percentage of gross domestic product to Ukraine’s war effort than any other country except for Denmark. Their citizens have also donated hundreds of thousands of Euros in crowd-funding projects to buy weapons and equipment for Ukrainian soldiers.

However, the key to success for Estonia’s fledgling military drone manufacturing sector has been the ability of companies to quickly react to battlefield demand. “Even the guy who was operating [the drone is sending feedback],” says Rikk.

“When they write to you at 2am, you have to be ready to answer them,” adds Tõnis Voitka, the co-founder of Krattworks, another Estonian drone manufacturer. “We have to face the truth—they are at war, we’re not.”

Consequently, the product development cycle for military drone designers can be as fast as 24 hours, explains Voitka. As Russia changes its tactics or develops improved electronic warfare systems, then so too must drone design improve or they simply won’t be able to perform their roles. Something that can cost lives, especially on medical evacuation missions.

Other problems, such as overheating have also been resolved, as well as the inclusion of the tactical awareness kit software (TAK), used by the U.S. military, and the Kropyva battle mapping software which is employed extensively throughout the Ukrainian army.

Krattworks fully appreciates the significance of the feedback in not only making better drones but in saving lives. For this reason, it is selling its Ghost Dragon reconnaissance quadcopter to Ukrainian units at a reduced cost.

Other modifications to improve the drones’ effectiveness, such as improved defences (as protection against artillery barrages) and adding night vision capabilities (as so many operations are safer to conduct in the dark), were also quick to be added.

Counter-jamming improvements were another urgent request, as the increased use of drones by both sides soon created an electronic war with Russia and Ukraine fighting for control of the airwaves.

In this instance, Milrem’s drones were better equipped than most. “THeMIS’s autonomous navigation is helpful in navigating while jammed as it allows the vehicle to plow on even without a signal from its operators,” notes the industry journal Defense One. “But it’s no easy task. Autonomous UGVs have to determine which bodies of water can be forded and which can’t, as well as which obstacles it can push through.”

Not that jamming the THeMIS would do the Russians much good, says Rikk, as the complicated software means that the enemy would gain little information if they were able to capture one.

“It's quite complicated,” he notes, “[And] it's not very easy to replicate.”

So, what can the rest of the world learn from Estonia’s experience of building drones for the frontline?

The importance of supporting Ukraine’s defence effort and hands-on experimenting is very relevant, as is real-world testing of electronic warfare systems.

However, perhaps the most significant part of the story is how drone design and manufacturing is being improved most through lightning-quick user feedback. For when it comes to a warzone, the customer may not always be right, but if he is fighting for his life then he can certainly tell you what he needs.

Photo credit: Wikimedia, Picryl, Wikimedia, Wikimedia, & Wikimedia